“Getting Dead” by David Collier

The only thing of consequence to occur in David Collier’s “Getting Dead” is just that, the death of Richard Collier – David’s grandfather and the subject/protagonist of the strip – and it’s a done deal by the end of the first page, if not quite an on-panel event then stated there as a fact, immutable. With his life established as something limited, complete, the next few pages go on to give the reader a glimpse of the circumstances of Richard’s last years: his suffering, sure, but how he lived as well, his home life with his daughter Muriel and son-in-law Hugh, his habits and daily rituals. Eventually the strip settles into a proper sequence, if not a story then a scenario: Richard heads off to the city to visit his son Trevor and his family, walks around the neighborhood, eats dinner, and a day later rides with Trevor to a farm Trevor is fixing up.

It took me a few readings to realize that this is all that really “happens” in the story’s 34 pages; the strip never puts too fine a point on anything of event, but it doesn’t really need to. It’s all just foundation for the real substance of the strip, Richard’s life, Richard’s memories rushing in, in no particular order, to fill in that rhythmic lull: Richard breaking his leg as a boy, the death of Richard’s wife Maude, Richard enlisting in the Royal Marines during WWI, and so on, all fragments of memory which come loose thanks to happenstance, stray association, and eventually become a ceaseless tumult that, by the strip’s end, adds up to the sum of one man’s life, more or less. Flashbacks occur within flashbacks, memory shifts sideways to entertaining and irrelevant anecdotes, allusions to other stories pass quick and unexplained – all of which is to say the story is a make-no-mistake ramble, at once urgent (in purpose) and willing to move only at its own pace, stopping and starting as it wants to.

That’s the jolly irony the strip exults in – how, despite the never-too-emphasized action, it just barrels along as a nigh-unbroken flexing of storytelling muscle, a momentum which doesn’t slacken from one panel to the next, guided along by the thread of continuity provided largely by Richard Collier’s gregarious voice. It’s a heck of a ride!

The present around all that may not be our focus but it is deliberate, a frame rife with finicky detail. Wanna know the route Richard walked between arriving at Trevor’s house and dinner? You’ve lucked out because Collier’s drawn a map. And what was the length of the distance he traversed? About five miles. At one point, Richard finds himself walking through a gay neighborhood and passes two women, one of whom is topless; it may or may not be a moment of interest for the reader, but it’s not for Richard, passing by, nor is it for David, who presents it incidentally, no overtones.

But it is there. That the present tense – this brief and not especially noteworthy segment of time – isn’t simply a springboard for Richard’s reverie but is as textured as can be gets at what’s unusual about “Getting Dead”, if only in relation to the stories surrounding it in Portraits From Life. Those strips all fall within a familiar template: Collier encountering a life, often some figure currently residing in footnotes (the Women’s High Jump gold medalist in the 1928 Olympics, the man who coined the term “psychedelic”) and recounting it mainly in broad strokes – experience and decisive actions, epiphanies, notable events, etc. Like Eddie Campbell (an artist Collier bears no small resemblance to), to depict reality means acknowledging the perspective from which it is seen, a notable degree of authorial presence, so a nice chunk of any given strip is made up of Collier researching, Collier discovering, Collier regaling. Collier gets a lot of formal play with this (e.g. juxtaposing his own story with that of the wrongly convicted David Milgaard in “Surviving Sasketchewan”, a diptych which can be read separately or in tandem, their corresponding page layouts roughly matching up) but the basic structure is very much set: the life seen and the observer, typically David, taking note of it – a strict sense of outside/inside.

“Getting Dead” is a bit more slippery. It begins as another iteration of that formula, if a little more freewheeling, throwing the reader into the deep end of its subject’s story – nonetheless Collier’s there as the reliable scene setter, partially as an on-stage presence but mainly as the dominant narrative voice, his familiar first-person guiding us along for those first few pages. Quickly enough though, he recedes waaay into the margins, subsumed – beyond the occasional digression or cameo – in the torrent of his grandfather’s life, his voice. From thereon, we’re left with Richard Collier, bound tight to the POV of a man who is both the story’s text and its interpreter, navigating each moment as it comes.

It’s not simply that the comfortable distance vanishes, that the narrative onus shifts from the author to the subject – the playing field of the strip has changed as well. What is, like the majority of comics, a story illustrated by time, time manipulated to give shape to an overall plan, also becomes something like an illustration of time. Or just one man’s perception of it, “it” being a moment both arbitrary and thoroughly delineated, sectioned off, something with no more significance than a set of footsteps which begin at one place (a train station) and end somewhere else (a farm) – we know what we’re seeing because we’ve already seen, in those earlier Collier-heavy pages, what it is not.

And what it is is not a story but many stories, enough to take measure of a man. That there’s not much in the way of a climax pressing upon us as we proceed – that things simply are – means that every moment seen holds the same rough value and, bouncing back and forth between the “then” and the “now” of one man’s life, time is not only a sequence but an environment, a field of play, somewhere where the reader can find herself suspended between every panel, every instance felt completely.

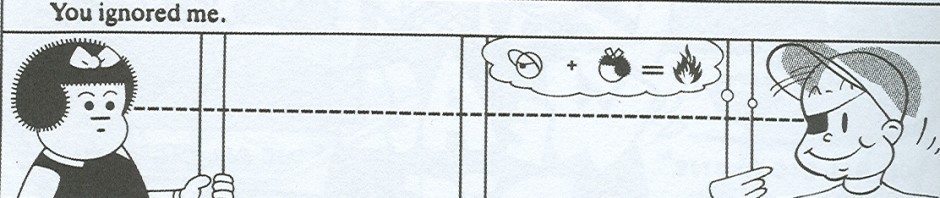

The sense of one man’s life has compressed to become, well, one man’s life and however large the past may loom, life is still happening, and it’s happening in the most obvious ways – morning exercises, rides across town, conversations over dinner; for two panels, the story gives way to a lesson on the proper way to hang toilet paper (with hanging strip toward the wall, not away from it).

But, of course, this is how Collier knew Richard – not as a set of texts excavated from the stacks, microfiche there to be mined, but as a man who had opinions on toilet paper, smoking (anti-), masturbation (pro-), and the best way to get rid of a blister, a very present old man happy to haul his history with him wherever he went. This is a life seen from the inside, a life speaking to itself as it’s being lived, fully inhabited on every front, the bold bulletpoints of the past and daily minutia of the present intertwined, everything of equal consequence as it probably would be to a man in his eighties or nineties, or at least to a man like Richard Collier, who at that age still very much partakes of whatever life will allow.

How could it be otherwise? From the first page, we’ve known how this story (if not the strip) would end – with Richard Collier repeating “Help me, Lord!” on a hospital bed – and everything else, as the title bluntly states, is simply a matter of getting there. From that vantage point, there’s no difference between the moment Richard displays the shrapnel lodged in his arm to one of his granddaughter’s friends at Trevor’s farm and the moment he receives that shrapnel, more than sixty years earlier in the disastrous raid on Zeebrugge in The Great War, the last memory Richard alights upon here, where he witnessed the slaughter of many of the men in his company and heard his commanding officer cry “Mother” as he died. It’s all past, all equal – at some point a voice spoke and someone, David or Richard, heard it and, later, repeated it.