(With a nod to Matt Maxwell)

I loved comics – I loved everything about them, and I was proud of the work I was doing, but I was ashamed to be doing it. You couldn’t admit to anyone that you were a comic-book artist. You had to say you were an “artist.” When people heard “comic books,” that meant you couldn’t be an artist.

– Pete Morisi, quoted in The Ten Cent Plague by David Hajdu

And one day you look at the opening panel of a comic from 1954 and see this:

The action in the background is a gimme, but the folks in the foreground are clearly the main event, far more vivid than the canned violence illustrating the caption, although that probably wasn’t the intent. The only reason these two appear on panel is to serve as an easy embodiment of seediness and low morals – key elements (along with the fisticuffs) of the genre this strip inhabits (crime) – and because the artist, wishing to establish a dive bar setting, found himself bored with the idea of drawing a counter in the background and instead opted for some impractical portraiture. Though they appear as a pair, I doubt they’re a couple, even in the desperate-closing-time-volley sense the setting would suggest. From the next panel on, the story keeps its visuals on a tighter leash, everything carefully aligned with the first person narration; action and effects taking a firm hold and leaving no room for anything like this man and woman.

As is, they already say so much there’s really no need. He says “I am an average piece of lowlife scum, getting my kicks from watching the show. Once it’s over and I’ve finished my drink, I’m headed off to commit some petty burglary and kill Ben Parker.” The woman, though it may not look like it, has plenty to say as well: “I’m numb to what’s happening in front of me and that’s exactly what I want to be.” “I have led a sad life, the details of which are depressing and familiar.” “I am a very effective PSA against drug addiction.” “If I lean back a little further, I will fall out of frame and land in a Charles Burns comic.” Add one more image of these two, another hint of their presence, and they’d be rendered mute.

As you’ve guessed, the epigrammed Pete Morisi is the culprit behind the above image, which is taken from a “Johnny Dynamite” strip he wrote and drew called “Kidnap”. Like most cartoonists of the time, he flitted from genre to genre – superheroes, crime, romance, with a special emphasis on western and horror comics – drawing and writing most, eventually amassing upwards of 300 strips by the time he lay his pencil to rest in the early eighties, a body of work which becomes a bit more impressive when you consider a) the consistent high quality of the work and b) his day job as a member of the NYPD for much of that time.

There’s not much evidence of any of that in the medium as is. “Johnny Dynamite” was resurrected by noir revivalist Max Allan Collins for an appearance in Ms. Tree and, in the nineties, a miniseries for Dark Horse but Morisi lingers around primarily thanks to Peter Cannon… Thunderbolt, a superhero he created in 1965 for Charlton. He’s a

character who may hit close to home for most readers, not because due to his tendency to be revived about every other decade – most recently by Dynamite (no relation) last year – but because he was the direct inspiration for noted charity gymnast and perfume peddler Ozymandias in Watchmen, a fact which ensures Morisi some continued presence, if only as a footnote dangling waaay below the text and commentary of everyone’s favorite white whale.* As for the real substance of Morisi, the work itself, it – outside of two stories collected in the Dan Nadel-edited Art In Time (where I first discovered him), some dedicated comics reprint blogs, and maybe an evanescent anthology or two – is properly preserved in the great polyvinyl purgatory or yellowing its way to Valhalla, somewhere out there.

“Johnny Dynamite”, which Morisi co-created with Ken Fitch scripting but quickly settled into sole authorship, was a series of crime comics starring the titular hardbitten one-eyed private eye, with a scale of values weighed far more toward “violence” than “sex”. It’s not an especially large part of his catalogue – it had a brief span on the racks, from ‘53 to ‘56 – but it’s prominent among what little we can see, the comics both formally and informally collected, and that’s not simply a quirk of the zeitgeist, the market for Mickey Spillane knock-offs not being what it once was.

And that is most certainly what they are, gleefully derivative caption-heavy first-person narratives, odd and incredible. The strips I’ve read shift to a high register after a single frame of build up and, five or six pages in, subside with a frame or two consisting of a forgettable resolution. Between those two points, you’ll find our eye-patched antihero, bunch of bullying thugs in fedoras, and some women virtuous or venal. The narrative complexity consists of “mix, serve, repeat.”

It’s an early fifties detective comic which happens to read like the concept of an early fifties detective comic, a pastiche of itself. By contrast, Harry Lucey’s “Sam Hill” (Philip Marlowe if you swapped out the wounded romanticism for cocky self-satisfaction), also featured in Art In Time, feels like another detective comic among many, never mind that it’s an extraordinary one and probably more satisfying overall than “Johnny Dynamite” – exquisite work tinged (as Dan Nadel points out) with a nice bit of Eisner, layouts which hum, a precise sense of space, and, as a cherry on top, character work good enough to harken forward to the glory of Jaime Hernandez. “Johnny Dynamite”, less than half a decade later, doesn’t truck much with such classical virtues – “story” here isn’t a goal but, seemingly, a pretext for Morisi to craft as many visual exclamation marks within the six, seven, eight pages allotted, perfect and airless bite-sized images. What levels out the anomalous duo who first caught my eye – a strong visual, simply presented – and the Fury (no Sound or SFX for that matter, simply, one imagines, because these images have no need for them) of most of the other images is a sense of isolation; the intro panel – that concentrated dose which opened most silver and golden age comics, intended to hook the passer-by into reading on – is, here, superfluous, nigh indistinguishable from the rest. Most given panels carry the discrete weight of a page in a Lynd Ward book, the only image worth paying attention to the moment you see it.

That you’d find this pictorial compression not carefully apportioned out in ye olde tradition of quality but in a work committed to all the crime for your dime, six frighteningly busy panel butting up against each other on a page, makes it one of the more curious comics you’ll find: hermetic, so damned assured of itself that it scarcely seems to need the presence of a reader. A straightforward reading leaves you feeling like you’ve just watched a movie with someone desperate to fast forward through all the boring bits. The canard against comics as fomenters of illiteracy seems appropriate , albeit here as a blurb.

The mention of “watching” isn’t arbitrary, insofar as the strip seems to owe a special debt to television, or at least attempts to come to terms with the televisual experience, its style easily read as a potent surface level response to the medium just then taking its wobbly legs out of the nursery. Most of the images hew to an exacting visual scheme – a user-friendly 3×2 page layout with the panels all coming with rounded borders (both appropriate to the first person past tense narration and unavoidably reminiscent of a TV screen) surrounding a medium shot or close up (always seen from an unwavering mid-level angle) with a depth of roughly three inches portraying some of the more inhospitably crowded compositions you’ll find. With its focus on the moment, too-clearly delineated planes of action, and panels almost uniform in size and shape, Morisi seems have created one of the few comics more suitable for a child’s Viewfinder than a page.

Implicit in this wonky and severe system, one which assures us the most hospitable view of the any given thrillpowered instant is, well, the viewer, a heightened awareness of the hypothetical space we occupy as lookers – to return to the earlier simile, you can practically feel Morisi jostling your shoulder with every panel as he pauses the screen to ask, “Did you see that?” It’s a self-consciousness which explains the distance, the instinct to gaze rather than read when encountering these strips. Action may supposedly beget action in “Johnny Dynamite”, but what’s more often felt isn’t consequence snowballing its way toward a climax but phenomena – perfectly executed gestures enacted within an iconographic template.

Image making supplants every other concern, leaving in its wake a string of moments bound together tenuously. The characters don’t inhabit environments but ideas, visual motifs: cracked walls, broken mirrors and windows, stray bits of expressionism doing time as matter of fact settings, each seemingly forty feet away from the foregrounded action, so space is mostly ad hoc, situational – wherever we see the characters is where they’re at, as the strip is basically illustrative (perhaps not too uncommon in the funnybooks of yore, the Golden Age of comics also being the Golden Age of Prince Valiant). Morisi, in “Johnny Dynamite,” has no interest in the naturalistic domain of “Sam Hill” (and 98% of every comic ever) and it shows when the action becomes intricate. A page-length scene in “Kidnap”, one depicting our hero finding a cache of diamonds on the docks and dealing out doom to a thug who stands in his way under a pier, aims to bound across the page, pulling us along like a more conventional comic would – you can tell something is up from the way Morisi has traded in the basic six panel layout for a neat build-up/climax/resolution internal structure; instead it’s kind of goofy, drifting from panel to panel with nothing to anchor the reader to the page, like a 1950s Greg Land.

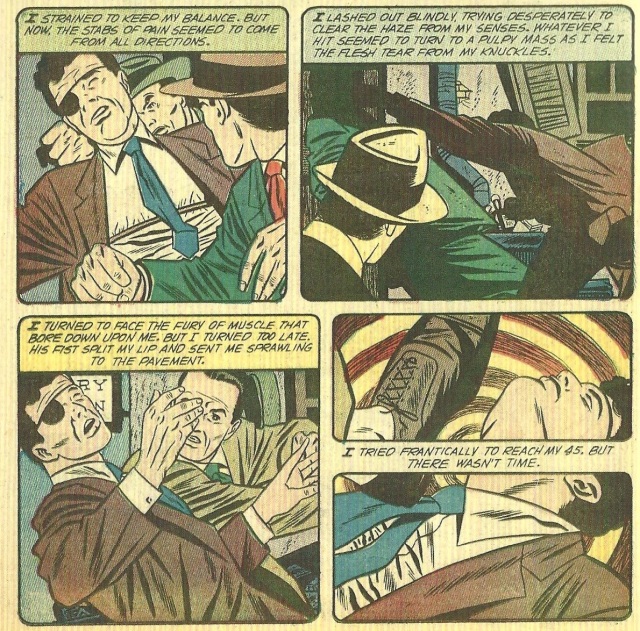

Thankfully, that grasp at nuance is an exception. It’s not always a memorable strip, but you’ll often happen upon things that stick like those folks at the bar. Something like, say, this:

Louder than words certainly, but I’ll give it a go. An individual comics page typically needs a price tag before it can transition from something story-based to an object, but this one announces itself as one the instant we see it. I want it. It may fulfill its expected function, telling its story like a proper unit of narrative, but mainly it simply is. My desire to engage with it in that way, to scan it for points of interest, is shortcircuited by its presence, the way it registers in one clean stroke, not as a series of images but as an image itself, something whole, never really pointing at anything outside of itself. Yet it’s not absolute; you could probably rearrange the sequence of panels at random and the effect would remain the same (this being one page among many, you could extrapolate that to “Johnny Dynamite” as a whole). It can’t quite be touched – it’s indeterminate, an idea, a phantom, hazy enough, I suspect, to stand in for both a comics page and an idea, maybe the idea of comics; a glimpse of something seemingly summoned up from the culture itself, with the caption and word balloons perfectly poised design elements speaking for themselves before they say anything (the fourth panel taking this notion to a gloriously self-conscious extreme), something they share with the Edward Hopper hallucination I first mentioned – no doubt, like a vast chunk of this essay, a reaction to mirages caused by the distance of time. And because it can’t be grasped, slipping as it does between the cracks of context, competing meanings, it stands, readier than most, to be anything – a postcard, a poster, this jpeg waiting to be clicked, blown up big for the sake of a gallery, whatever – and will remain always itself, its effect undiluted by its surroundings.

“Johnny Dynamite” feels most often like a sideways step away from the expected form good or great work often falls in, away from the unified aesthetics of Eisner or Kirby or Cole or insert your own favorite, where craft and technique build up over time into a coherent chapter in a textbook. It’s exciting and boring and oddly sublime, all those qualities at once, but what’s especially notable is that damn destabilization that can’t help but pop up, something which we might consider as much a part of Morisi’s legacy as the vagina monster which destroyed half of New York. This self-consciousness, the frame of recontextualization which sometimes falls upon these images (which, for Morisi, was probably a trapdoor, unintentional) prefigures a lot of what would come in the decade that followed, all the “Pop” or just plain pop which approached its subject like a mathametician breaking his brain on an equation called “charm”. Things of this sort – soulless and terribly seductive, neat exercises in aesthetics which engage the viewer like the most stylish and self-aware wallpaper imaginable, which, come to think of it, is a good description of Pop Art. And speaking of wallpaper designers, I’d be remiss if I neglected Lichtenstein, the White Elephant in the room. Looking at Morisi, you get a good idea of the initial thrill of Lichtenstein, the excitement of seeing contexts violated, a quick sensation of boundaries become porous; but if Morisi remains porous, antsy, continually unstable (which Warhol occasionally manages as well, especially in his film work), Lichtenstein, beyond the obvious gimmick of carting an image across a presumed high/low boundary, carries a harsh aftertaste, his cheeky razzing of the hierarchy, in the end, affirming the standards of that hierarchy, with the barriers emerging all the more resilient. We may more profitably consider Morisi as a precursor to Steranko – working with a zip-a-tone none too bloated to produce the most wondrous surface effects, with genre as both his content and his canvas.

*We can connect even more dots if we glance at Thunderbolt’s pedigree as well; originally, Morisi intended to revive the golden age superhero Daredevil (not to be confused with the Marvel character), the same Daredevil launched into popularity by Jack Cole in “Daredevil Battles The Claw!”, a boomerang-wielding vigilante-type who wore a cool blue-and-red symmetrically patterned bodysuit and a charmingly superfluous spiked belt. When rights issues stalled, Morisi kept the costume design, simply uncovered the head, dropped the spikes, left the bodysuit barelegged, and added a whole mess of Eastern mysticism – ergo Thunderbolt.

It goes without saying that this Daredevil has also been relaunched by Dynamite recently.