I.

Let’s start with superheroes.

The idea had been kicking around for a few decades – in science fiction, the pulps, embedded, perhaps, in the already popular supervillain, who did boffo business in a Europe undergoing the birth pangs of the new century, with Fantomas, Dr. Mabuse, Les Vampires, et al., arch-manipulators all, as scapegoats the primal imagination could, in books and movies, shake something fierce for cathartic effect. Anyway, cultural forces aligned, global catastrophe loomed, and so, in 1938, Jerry Siegel and Joe Schuster ushered Superman onto the scene.

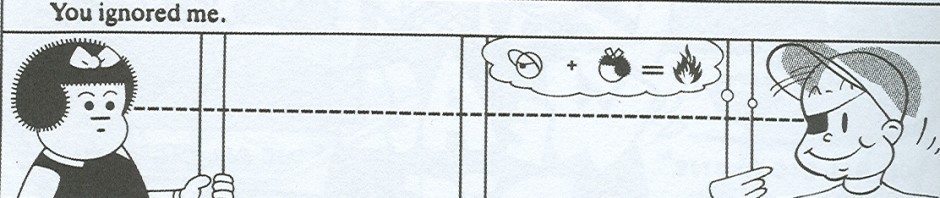

Or, more precisely, a scene arose in response to Superman. What came before in the comic book – the format where he premiered and which he remains largely identified with – can be easily summed up (said format being all of four years old) as reprints of syndicated newspaper strips, licensed knock-offs of said strips roughly akin to coloring books in terms of ambition (cruel reminders of where the medium was really thriving, its natural habitat both popularly and artistically; well, it would be cruel if anyone involved cared, which no one really did), along with original material – by artists who were, de facto, not good enough for the syndicates – there to fill out the page count, something which became more prevalent when publishers became eager to cut syndicates out of the equation; there were, no doubt, tiny pockets of quality in the midst of all that, seeds spread on uncultivated ground, quick to be swept away in the wind. Dent in the culture caused by someone faster than a speeding bullet notwithstanding, the comic book stood its ground as the shabbiest and most benighted spot on the artistic landscape (“A couple of steps below digging ditches,” per Jokin’ Joe Kubert), though understandably more lively, “gold in them thar hills!”, etc.

The Greg Sadowski-edited Supermen!: The First Wave Of Superheroes anthology is a nice look at that ground zero, the creators who came in the wake of the Man Who Came From The Sky And Did Only Good to meet the public’s sudden demand for More Of This. It couldn’t remotely be comprehensive, of course, the first obvious limitation being “Whither the icons?” In your dreams and on your lunchbox, copyright DC Entertainment, a subsidiary of Time Warner, all hail Mithras, etc. Anyway, that’s sort of moot, the book’s focus being more anthropological, favoring in its selection the spectrum of quality over the apex – what we would see on the racks before we knew exactly what we were looking at, when the artists themselves may not quite have known what they were aiming for.

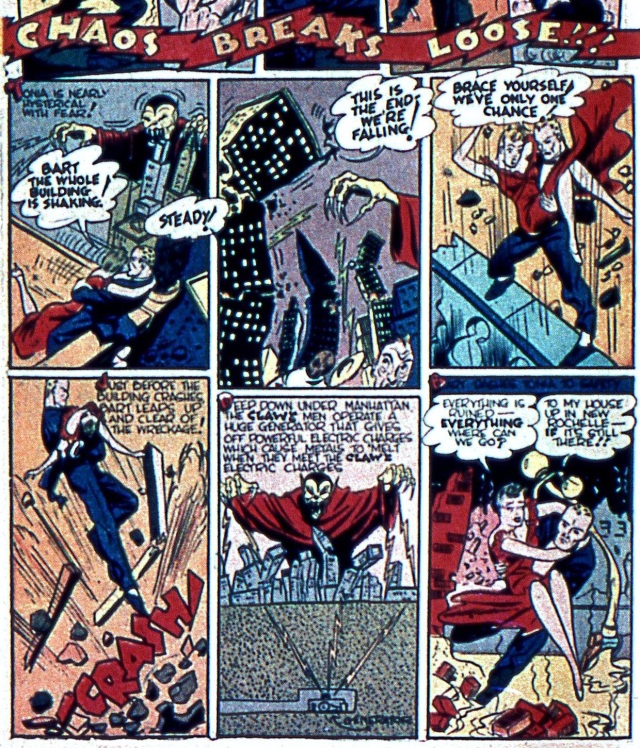

Of the specific impressions the book leaves behind, none registers quite as strong as the monstrous assuredness of Jack Cole, one of the few artists included who needs no qualifications and is worthy of all hyperbole. Beside the odd sketch-like quality much of the book assumes from our point of view, Cole’s work not only shows whatever promise the superhero genre may have held but fulfills it. It doesn’t define the form but it adds definition to what was already present; while it’s hard to shake the scrim of the present when looking at the earliest Superman and Batman stories, whatever their virtues (a blunt and straightforward charm and an amphetamine driven primitivism, respectively) – the process of iconography so clearly at play, what works getting set in place and what doesn’t being quickly tossed – you could possibly unpack the entire genre from Cole’s “Daredevil Battles The Claw!”, a rollicking rampage of a strip contemporaneous with all that which reads less like a story and more like a crackling bolt of momentum.

But it could have been any genre with Cole – it’s just happenstance that it was one not done gelling, with physicality as its apparent explicit dramatic engine (it’s very possible that no one in the genre since has used action to bridge one moment to the next better than Cole). What’s unmissable is that we’re watching an artist at the onset of a nascent form – the long-player comic – approach it with techniques fitted to suit, contemporaneous with Eisner and Kirby and Bill Everett but, relative to them, almost fully formed; an understanding of the page as a coherent unit of story rather than a convenient collection of pictures, moving from panel to panel with storytelling so powerful that the comics seem on a race to read themselves faster than the reader can. Jack Cole!

You won’t find much else like that in Supermen!. There’s other good stuff though, a few straight-up oddities (more in a bit), as well as the decent and the boring, along with a few strips that may very well break your brain (let it be known that Gardner Fox on script could inject a bit of pep into a humdrum comic). Nonetheless, it’s all bold in one way or another, crafted as it was during the brief moment before the genre became codified, when the only gestures permitted were bold gestures. It accrues a bit more significance when you take in a wider view, this being arguably the moment when what we recognize as the current American comics scene comes into view; not to equate Superman, whether he’s duking it out with unionbusters or the descendants of Jerry Siegel, as the alpha and omega of the medium, but he and the host of capes quick to follow were the kick in the ass multiple-page comics (now oft-gussified as “graphic novels”), comics not sandwiched in the (then) secure domain between Arts and Leisure and the Obits, needed to be taken as a contender in the market, standing as they do victorious today.

II.

Sadowski posits the arrival of Simon and Kirby’s Captain America in late 1940 as the end of that free-for-all period, a good choice; surely something about the genre solidified when a cover was bold enough to show the hero socking Hitler in the jaw, when the genre felt confident enough to bypass the metaphors for the anxiety which fueled it – aliens, crooks, sorcerers, absurdly racist Fu-Manchu types, et al. – and went straight for the real thing, especially when that comic sells a million copies in the span of a heartbeat. Superheroes would wax and (particularly after the war) wane, while other genres took the lead – crime horror, romance, the once-bustling saloon known as western comics where no one sits a spell anymore, empty of any liveliness but for the tumbleweeds which sometimes blow past…, etc. (with kid’s humor books somewhat sectioned off into a realm of apparent happy market stasis – hey, Archie!) – with booms and similar moments of intense experimentation, but now with a hard-won infrastructure around them to quickly quell any chaos, to set things aright for the sake of maximum profit, a familiar fable of capitalism. I look forward to reading those anthologies.

If Cole gives us an idea of what would be embraced and assimilated (as was Cole himself, grand scheme-wise, going on to write and draw a run on Plastic Man in the forties which remains an easy pinnacle of the superhero genre and, maybe, the medium, as well as, in a crime comic, drawing the single greatest panel ever printed, so deigned by the New York State Legislature), Fletcher Hanks serves as a convenient embodiment of what wouldn’t quite, what might have only seen print in that happy hectic gap; mind you, there’s no real way of verifying hindsight in this case – if Hanks’ career in comics didn’t last primarily from ’39 to ’41, perhaps (let’s say, with extraordinary qualms) he would have exerted more influence. As is, that’s hard to imagine – like Cole, he seems to have come fully formed to the genre, though “fully formed” in his case isn’t so much praise as a statement of fact, what you see being what you get. You’ll find nothing like Cole’s skill (or talent, for that matter) in Hanks – his work is crude, simplistic, and, oh so importantly, awash in all the raw power of a Contra boss battle, a quality he wields in a mighty and monotonous manner. The typical Hanks strip follows like so: bad guys, whether they be aliens, gangsters, or whatever, are up to the worst shit imaginable – the destruction of all life ever, probably – and it’s up to Stardust, a nigh-omnipotent “super wizard” (that the language has yet to settle carries a surprising charge of disorientation) who resembles a ‘roided-up Marvelman, to rain down from the cosmos and smash evil flat. If that sounds like a six year-old’s power fantasies, the hard product themselves read like a six year-old’s power fantasies fine-tuned by an outsider’s hand for the sake of maximum intensity, which is where Hanks’ left field status comes from; the comics feel a step removed from reader identification, nominally “escapist” but really just an equation of power and destruction and apocalypse compulsively worked out, heedless of a general audience, but not dandy aesthetes like myself – we gobble that shit up, as evidenced by the Hanks revival of the past few years (can a corpus be “revived” if no one took notice of it in the first place?). You can get a taste of his work in Supermen! and find it, probably in its entirety, in the recent collections I Shall Destroy All The Civilized Planets! and You Shall Die By Your Own Evil Creation!, the emphatic exclamation marks telling you all you need to know about their content, though you can spot Hanks settling into his own formula by that second collection. At its most potent, it seems both childish and vast, inhuman, dense with off-hand surrealism and ever-escalating fury, stuff far afield from the standard of yesteryear, whether it was Cole or, say, Flash Gordon.

Basil Wolverton, another Supermen! alumnus, easily juts out from whatever random sampling of artist you lump him in with. Relative to anyone mentioned thus far, he might be less in need of being cradled by a curator from the back issue bin to the reader’s attention – whether you read comics or not, chances are there’s a trace signature of his work buried somewhere in your brain. His work begins with a jolly sense of caricature and from there proceeds – or really just leaps head on – into the gleefully grotesque, the ingenuity of his doodling strong enough to leave narrative behind altogether so the images frequently justify themselves. Like Brian Bolland, Wolverton’s pictures come as crisp as can be, seemingly bemused by their own presence and the onlooker’s awareness of their presence, carrying their own frame around with them, so strong they flatten not only content (“How the hell can any story live up to that?”) but context – the images treat genre more as a vessel of conveyance and identify mainly with the quotation marks they hoist high on their mast. Also like Bolland, the fact that he wasn’t exclusively an illustrational talent remains a continual surprise; he actually was there, doing time as a journeyman, with, relative to whatever hapless work besides him in a ten-center, an emphasis on “journey”. Humor was his natural wheelhouse – Powerhouse Pepper in the late forties and tattooing himself on the century as a key element in early MAD – but he ventured into other genres: sci-fi (“Spacehawk”, included in Supermen! despite not being remotely a superhero comic – one imagines Sadowski simply couldn’t pass it up) and some swell horror; Wolverton’s presence in these stories – nice meat and potatoes stuff, which play it as straight as can be – can’t help but make them seem like implicit commentary, winks at the reader.

If Wolverton is out of time, the illustrations irreducibly themselves regardless of when you see them, Matt Fox’s work must have seemed like reprints the moments they hit the stands. Fox, like Wolverton, was about a decade older than the typical comics pulper of the time (and both of them a few decades younger than Hanks!), with a similar habit of rendering images as defined as any you’ll find, annihilating the idea that they could appear otherwise the instant you see them; the art isn’t so much drawn as engraved, the average panel doing double time as both narrative cog and near self-sufficient illustration, often tableau-like, with no detail therein subordinate or half-assed. Fox interprets his material – almost always horror damn near resolute in its unremarkability (tending as they do to twist endings visible from the second panel, if not the first) – with the gravity of a child’s nightmare, his imagination apparently inverse to his dead seriousness. The time is night (and probably later than midnight), the monster is a monster, the vampire arises from his coffin to be framed by the full moon, the sinister house down the lane (with the same full moon attached) is where doom awaits… all with nothing remotely like Wolverton’s wink, nothing resembling irony, or suspense for that matter. Golden age horror is rife with this hand-me-down imagery and the end result of Fox’s work may be just as naïve, but it resists quaintness – the determined weight of these images, combined with a storytelling simplicity which, at times, veers close to the Stations Of The Cross, instead makes them seem eldritch, genuinely uncanny. Often the temptation is to bypass critical evaluation altogether and just see these stories as instant relics, curious artifacts recovered, their original purpose as entertainment overcome by their immutable presence. (We will return to this.)

This list could go on for a while. The point isn’t quality but the sense of something hopelessly askew – after all, there are other cartoonists of note from this era who never strayed: titans like Kirby or Cole, who couldn’t stray insofar as they defined the path, their footprints either guiding the way forward or massive enough for many to comfortably play in (perhaps indefinitely); extraordinarily storytellers, deft in their economy, content to get the job done and get it done as right as it could be (“Good Duck Artist” Carl Barks; Bob Bolling on Little Archie; Jesse Marsh, who seems to have spent nearly two decades doing nothing but producing panel after perfect panel, most of them for Tarzan; etc.); and a variety of other categories, names bandied among aficionados. Whether it was a bit of “What the hell was that?” by Hanks or some sophisticated schtick from Wolverton, this is all eccentric or quirky work in an environment designed to quash quirks, work which arose during a mid-century moment when production, set at an industrial pace, fell into a well-regulated process: an artist – often required to adhere to a house style which ensured both a company-wide consistency and his or her easy replaceability – and a writer (mostly, though not always, separate) working to craft product which did what was expected and filled out whatever generic framework was selling that quarter, with quality less a secondary concern than incidental – presuming the job wasn’t already farmed out to a shop of artists, reliable and faceless, in the first place. However threatened the suburban landscape of the early fifties may have been by innocents who’d heard one too many Tale Too Terrible To Tell (“Wertham’s Whelps”), those stories were meant to sell to a mass audience and meant to sell well.

III.

Superheroes returned to the fore in the early sixties to dissolve the convenient frame of this informal inquiry, the one they’d first built. We can maybe see the presence of Steve Ditko at the center of the medium for a few years – an artist as peculiar and singular as anyone I’ve mentioned, prone to gawky images told with an odd hypnotic grace, environments set either as elegantly sparse geometry or patterns of pure form, some of the most precipitously anxious moments committed to a page, and too many other qualities to go into here – as a sign that this concentrated moment had dispersed. Other markers come quick after that: Steranko exploding genre into a series of effects, the rise of the underground, Eerie and Creepy making the traditionally modest horror story in comics into self-conscious authorial gestures, various et ceteras. Ditko soon enough traded in Strange Tales for strange tales, willfully (or rather Willfully) inhabiting the margins familiar to anyone who’s read this far. You can draw whatever conclusion you like.

Pingback: Need To Know… 28.10.13 | no cape no mask