OR:

This may, dear lord, be the first in a series of posts.

For a while now, I’ve been interested in the work of Mark Newgarden. The keen-to-the-scene observer might have first noticed him in the underground comics of the eighties, specifically the RAW division of said milieu, his work apiece with the antiseptic conceptual acrobatics that dominated the American contributions to that now-hallowed publication – R. Sikoryak’s restructuring of the eleventh-grade reading list into the tropes of golden oldie comics, Spiegelman’s family history vs. HISTORY filtered through the scrim of animal roles, etc. (Don’t worry – Panter, a key part of that pantheon, had enough condensed murk to make up for it.) It was (and remains) a common tactic in comics – taking items out of the ever-increasing cultural toybox, particularly those toward the bottom, the more disused the better, and seeing how they held up in the more idiosyncratic playground of the Now (or, at least, Then). Newgarden’s another of this ilk, albeit less inclined to a one-to-one relationship between form and content than those mentioned above, more likely to dig into a context, assume all the given qualities, and manipulate it to his content. You can find the bulk of his work in We All Die Alone, released by Fantagraphics back in 2005; it is a book so gorgeous in design it will make all the other books on your shelf plot its demise.

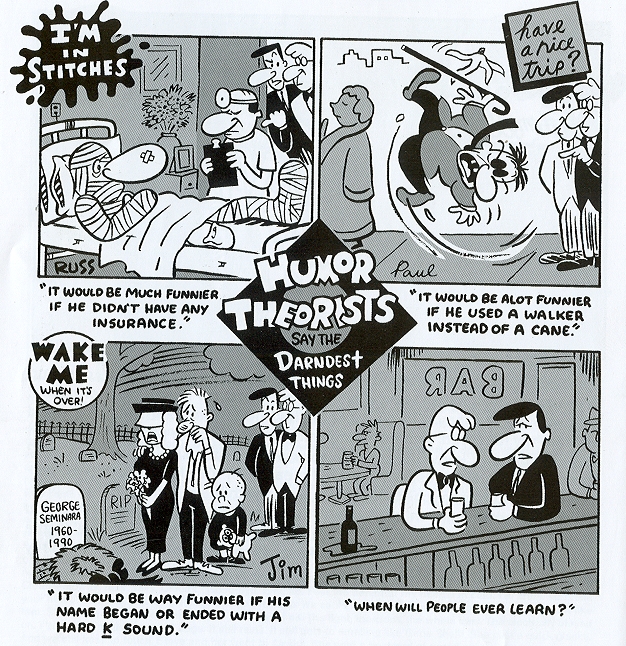

Newgarden is a very much a formalist, a man on a mission of pure aestheticism.* You might compare him less to Sikoryak or Spiegelman and more to Richard McGuire or even Yuichi Yokoyama, dedicated to the single gesture intent upon illustrating a theory in action, but muddying those waters of wondrous aesthetic detachment by placing “entertainment” at the center of his thesis, humor specifically, with a special emphasis on gags of the everyday ephemeral variety which were prevalent from the early twentieth-century until sometime in the sixties, the vultures beginning to circle around the time MAD first saw print. Despite staking this more rarified ground – a sensibility marked by well-endowed secretaries being chased around desks, big noses as an axiom, and clowns as catalysts for genuine laughter and not dread – Newgarden is not a man out of time, with irony, the reason for the season, as the engine of his work, here put into overdrive within a form often manufactured on the assembly line and built for hermetic self-sufficiency and immediate disposal.

His art style follows suit, channeling all the caricatural tics of an earlier era in an ad hoc readjustment from strip to strip, dependent upon the mode being pastiched – readily leaping onto a generic style and then programming it to devour itself. Or, of course, resorting to good old cutting and pasting. My own powers of squinting are far too weak to discern the stylistic signature of the man beneath all those masks, probably fitting for a fellow prone to signing something other than his actual name on his work.

His early and more sporadically released work (Pud + Spud, What We Like, etc.), despite all the mordant yucks and non-yucks on display, revealed his overriding preoccupation to be rhythm – repetition, the motif played across the page and elaborated; the aesthetic aftertaste is of a set of pre-selected still images played on a grid, themes and variations of those themes bouncing off each other in a frenzy. Those wee eye-straining tour de force strips that Chris Ware inserts at the slightest impulse, tiny and epic portrayals of time and process, owe a bit to Newgarden.

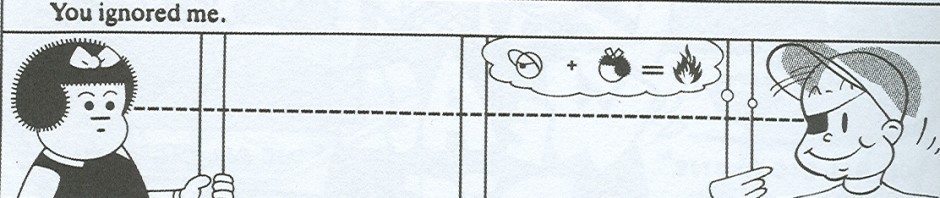

He reached an apex in Love’s Savage Fury – there’s a few pages of notes right next to my computer telling me I have a bit to say about it, enough to destabilize this little jaunt, so, in my duties as your tour guide, I’ll just point it out, right outside the window, as one of the more mighty monuments of postmodernism you’ll encounter. It’s a four page saga of Time Lost and Time Regained starring Ernie Bushmiller’s Nancy and Bazooka Joe which initially flows like a bit of poetry and grows in rigor and ambiguity with further readings. It’s earned most of the superlatives already thrown its way and wouldn’t falter from the weight of a few more. I’ve nicked a panel from it in for my header, to greet the wandering googler and maybe cajole them into laying their head here a few minutes before they, astutely, abandon it for one of the better and more frequently updated sites, with less cobwebs and more Batman.

Love’s Savage Fury seems to have been a sign for Newgarden, though, warning of impending diminishing returns. A familiar dilemma: can’t stand still, something would need to change. Your Snappy Pals seems representative of this, a series of strips which seem to exist solely for the sake showing off odd rhythms, pure fucking around; each of these strips depicted an awkward or nonexistent conversation between a tall bird-like figure and a polka-dotted faceless little man, both standing at the same fixed points over a dozen or so frames. We’re not far from Tim-and-Eric territory here, playing with an audience’s expectations by inserting deliberate off-beats in the timing and burying the punchline deep or tossing it out altogether.

This specific approach – the punchline and, oh, the wondrous contortions it could take – would come to the fore when Newgarden undertook a syndicated weekly strip (appropriately titled Mark Newgarden) in New York Press from 1988 to 1991; fucking around of a different order is required when you’ve got a deadline to meet fifty-two times a year, naturally.

Formalism would still be in place, but it would be streamlined, less jagged, with an easy-to-grab hook readily at hand. Newgarden would burrow into those forms that were never so much old as nearly stagnant from the moment of conception and turn them inside out with a revolving-door format of tropes – blunt and bleak gag strips, illustrated absurdist monologues and lists, and occasionally eschewing the graphic format altogether (“NOTHING FUNNY THIS WEEK.” Etc.); “anything goes” seems the appropriate phrase. This phase, and thus most of Newgarden’s work as we know it, is perhaps most potent when seen as a whole, the strips less fully-formed works than segments of a three-year long performance, a jolt of termite art reeking of sweat and inspiration tossed off on a regular basis, and onto the next one. Perhaps it’s our privilege, denizens of the golden age of reprints, to see it in something closer – most, but not all, are reprinted, nor are they presented in chronological order – to it’s ideal form.

So for right now, I’ll focus on one of my favorite of Newgarden’s pre-syndication comics, “Draw Your Favorite!” It’s a piece which has thus far escaped the recent spate of library-bound anthologies, so, assuming you don’t have a copy of Bad News #3 handy, released way back in 1986, your only hope of seeing it in proper tactile form is We All Die Alone, but, hell, even there the strip escapes the “Content” section proper, only noticeable in the margins, as an illustration accompanying Dan Nadel’s introductory monograph; a notch above the strips only found in the endpapers, at least. In light of that absence, you might see it as a genuine piece of ephemera among faux approximations of such, an assessment which especially disheartens considering the twelve pages the book allots to, y’know, toilet paper wrapping. But should this strip need a champion, indulge me a tin-can suit of armor, a wooden sword, and a trashcan lid shield. (And, within that metaphor, my own little irony: as everyone knows, the only real way to appreciate comedy is via the lens of the microscope, its pulse inverse to the acuity of the critic’s perception.)

“Draw Your Favorite!” is a delightful formalist exercise, the premise for which should be obvious from the image posted above. NONETHELESS: it’s a jolly merging of both characters and process from the correspondence course art class ads of yore where, presuming the reader could muster enough talent to render the headshot on display, the materials to foster said talent into a viable career prospect (maybe?) would only be a check or money order away (and perhaps a self-addressed stamped envelope, I imagine). Here two of those headshots, Cubby and the Pirate, share a bartop, act according to their skin-deep personas (soused glee in Cubby’s case and grouchy menace emanating from the Pirate), and the situation crescendos into wacky violence, the falling action being Cubby’s immediate dissolution back into draft stage in its wake, the blood registering with less impact than the regression. On the surface, it’s simple comic juxtaposition, close to Sikoryak, with a well-executed premise doing all the heavy lifting for the reader’s attention – rev up those concepts and watch ‘em go.

But that’s only part of what’s going on; a closer look and what initially seems like a gimmick reveals a taut internal logic, with content and form even more intertwined. Notably, the characters’ interactions occur only when they’ve reached fully rendered form, the climactic confrontation throwing a light upon the careful off-synchronization of the two central figures, with the pirate played one beat behind Cubby to ensure everything is timed perfectly – the author’s hand, already on display in every panel, is just all that more present and what seemed only an ingenious illustration of a technique shows itself entangled in structure. Form follows function.

It’s a remarkably neat strip, registering less as a story and more as a piece of music, a limited set of elements introduced and then performed. Every facet works perfectly in tandem: the technique of Draftsmanship 101 adding texture and clarity, stage by stage, to every panel, compelling the eye to zoom from one moment to the next, with the dialogue, thought balloon-bound or no, functioning primarily as a rhythmic effect, a lively and steady beat – Cubby and then the Pirate, repeat; we know we’ve reached a climax when that beat is upset. In terms of storytelling clarity, it could be considered a slightly elaborate illustration of Freitag’s Triangle.

Plus, the bear just makes me crack up. Look at him!

It wouldn’t be the last time Newgarden would grab a piece of iconography and reframe it as he saw fit, obviously. More to come on that, folks…

Or so I hope.

*Not to say that the impulse toward bottom-of-the-line entertainment wasn’t present – after all, Newgarden is responsible for the Garbage Pail Kids, and thus an easy candidate for pop cultural canonization.

Good work. On some level, isn’t humor really ALL about rhythm? Pauses, repetition, tempo…these are what make unfunny things funny and, as evidenced in abundance, potentially funny things deadly unfunny. In turn, a dead ear does not permit a reader to understand why something like, “What We Like” is funny as hell.

The more that the world knows about the work of Mark Newgarden, the better place it will be…however we shall all still die alone.

Thanks for commenting, Paul! Your “good work” does indeed raise my spirits, considering I’m a pretty nascent writer – my critical apparatus would probably be best described as a twig fishing line with an apple core attached to the rusty hook at the end of its line.

W/r/t rhythm, you are absolutely right – the crux of comedy boils down to rhythm. I was just trying to identify, in my own careless way, the x-factor that defines all those early pieces up to Love’s Savage Fury, at least relative to the differing approach of his far more punchy, less ornate weekly strip (barring, of course, the classic comic antics of The Little Nun). I can only hope that I came within ten miles of my goal.

“The more that the world knows about the work of Mark Newgarden, the better place it will be…however we shall all still die alone.”

Well said.

Mark Newgarden is the Donald Barthelme of comics.

That’s a pretty good analogy. When I was a kid I tried to read Barthelme as if he were Perelman or Benchley, with the expected missing of some important points. Lumping his work with that of the ZAP guys many years later (“retro” style with postmodern twist) was similarly inadequate. Mark is *sui generis*, and he deserves to much more widely read than he is.

I’m telling Kaz on you.

Great essay, and I hope you write more about Newgarden. In my “backpocket” set of long-form essays I plan to write one day, I have one called “Newgarden/Friedman: Abstract/Concrete”, about the ways in which Newgarden and his friend Drew Friedman draw from the same sources and choose completely different methods with which to execute their ideas. I get a very similar feeling when I read the work of either cartoonist.

@PaulKarasik: All humor is based on rhythm, to be sure. Most humorists prefer to make that rhythm hidden, not wanting the reader to see the apparatus behind the joke. In Newgarden’s case, the rhythm IS the joke. It’s like listening to a Mingus record.

Thanks, Rob! I’ve only recently come to admire your own work, due to the Journal.

I do hope to write more, and soon, time and circumstance permitting.

All I know of Friedman is “He Had A Funny Face”, which, over the past month, I seem to have picked up in two different pubs. – Brunetti’s Anthology Vol. 2 and Raw, Vol. 2, #2. That comparison you make compells me to keep diggin’!

Thanks for the kind words.

I’d take a look at “The Fun Never Stops!” from Friedman, which is the work I plan to work with.

Pingback: Slumberland | It's Like When A Cowboy Becomes A Butterfly